A Streak of Sadness

What Elizabeth Goudge is teaching me about depression and despair

“I believe the right books find us at the right time,” a former professor of mine likes to say. It’s true. The right books find us at the right time and they speak to us in the right ways. Some books sit with us for years, bringing wisdom in each new season until they become old friends. Some books wait on our shelves until we finally notice them, which always turns out to be when we need them most. Other books strike like lightning.

Elizabeth Goudge’s A City of Bells struck me like lightning. It found its way to me via a dear friend, who gifted me a lovely old copy: sea green boards, yellowed at the spine, the pages the perfect weight and sandy shade, every serif letter pressed into sentences that march across the page with staffs and branches. I’ve been reading it slowly, a page or two before bed. Not because it’s a hard read—not technical philosophy, I mean, or dense theology—but because every page cuts deep. Sometimes you start a book and realize, a chapter in, that this book will change your life, and so you slow down, you read every line over and over again, you savor scenes and images so that every potent word can slip into your inner life and take root. (The Brothers Karamazov was one such book for me, and The Four Quartets, and Jane Eyre the last time I reread it.) Like a pair of tinted sunglasses, the book starts to color your world—you see through its images, think about things in its phrases, assign characters to the people you know. These books not only entertain us; they teach us how to think about the world. (Coleridge, and many voices after him, would say such books shape our moral imagination.)

Sometimes you start a book and realize, a chapter in, that this book will change your life, and so you slow down, you read every line over and over again, you savor scenes and images so that every potent word can slip into your inner life and take root…Like a pair of tinted sunglasses, the book starts to color your world—you see through its images, think about things in its phrases, assign characters to the people you know. These books not only entertain us; they teach us how to think about the world.

A City of Bells is changing my life. I can’t write that sentence in a perfective past tense— “changed my life”—because I haven’t finished it yet. Slowly I read, slowly I savor, and slowly its characters take root in my moral imagination, changing how I think about myself and my world. The book contains delightful dramatis personae: wise, tender-hearted Grandfather, whose artistic mind and care for others reminds me of my own father; practical and sharp Grandmother, whose English archetype finds many parallels in my Midwestern family; sensitive Henrietta and vivacious Felicity, reminding me of so many of my friends, women who, whether quiet or exuberant, are lovers of beauty and life.

But there are two characters with whom I myself identify. First, the protagonist Jocelyn, a young man who arrives in the city of Torminster as a weary veteran of the Boer War. He quickly falls in love with his Grandfather’s small cathedral town and opens a bookstore, at the prompting of his young cousins and the actress Felicity. Surrounded by his whimsical family and the endearing townspeople of Torminster, Jocelyn almost fades into the background as a protagonist—he’s quiet, acquiesces gently to his child cousins, and spends the first half of the novel pushed around by circumstance. He ends up in Torminster, wounded and weary from war; he ends up keeping a bookstore at the insistence of his family; he ends up with a dog named Mixed Biscuits courtesy of Felicity. But as Jocelyn stays in Torminster, his story becomes entangled with that of the poet, Gabriel Ferranti, the previous owner of Jocelyn’s house who vanished from the town. Jocelyn finds an unfinished poem of Ferranti’s and decides to complete it himself. As he composes, weaving his own verse into Ferranti’s, he begins to see the world through the poet’s eyes. He asks the question: “How is it that artists keep their powers of perception even in the days when life darkens?” And he arrives at this answer:

“…He thought their perception was born of the faculty of wonder, deepening to meditation and to penetrating sight and so strong that it could last out a lifetime. Grandfather wondered, all day and every day, at the wisdom of God and the beauty of the world, and Ferranti had wondered at the waste and pain and frustration of life…The verse that expressed it was vivid as lightning and cruel as a microscope in its power of enlarging horror…Night after night and during every spare moment of the day he steeped himself in Ferranti’s poetry, and in all poetry that seemed to him akin to it, and he tried to feel every trivial happening of the day acutely and see every beauty and sorrow trebly intensified.”

As Jocelyn tries to see the world through the lens of Ferranti’s poem, his own poetry changes and grows more like that of the tragic genius he studies. This change happens unconsciously, even as Jocelyn feels himself inadequate to finish the poem, but when he reads his completed version at Christmas, Grandfather tells him that he cannot tell where Ferranti’s verse ends and Jocelyn’s begins. The poem is a story about a man who searches for the perfect form of Beauty everywhere in the world and only realizes at the end of his life that he has already glimpsed Beauty in every ordinary thing he disdained along the way. Jocelyn could finish the poem because as he “steeped himself” in Ferranti, he took up the poet’s passionate search for Beauty in the horror of the broken world, and learned to see with the poet’s eyes everything he encountered. He becomes Ferranti, in some ways; there is a doubling between their lives even as his verses merge with the other poet’s.

But Jocelyn already had a kinship with Ferranti, even before finding the poem. Grandfather says about him: “he has a streak of sadness.” Jocelyn himself, comparing his personality to Felicity’s, said:

“Those warm lovers of life, born under dancing stars, how without them was life tolerable for those, such as himself, whose bias was towards sadness, their stars cloud-hidden when their spirits woke to life…In this world, surely, there should always be a mating between the lovers of life and the endurers of it, in couples they should find a causeway for their feet and walk it together, the star-shine of the one comforting the darkness of the other.”

Reader, I cried when I read those words. I felt like I’d met myself for the first time, face to face.

Let me explain.

“Autumn is the hardest season for me to love. Summer is my favorite, full of warmth and water and the open-endedness of unorganized time. Spring speaks of returning light and the new life of upgrowing things. Even winter is made bearable by the celebratory interruption of Christmas, always, for me, associated with the color gold: strands of lights and king’s gifts and pictures of the Christ-Child haloed and announced by the bright Bethlehem star.

Autumn also has its moments of light and grandeur—the fiery leaves picked out against the clear sky or whirled like marigold storms above the sidewalk, the deep orange of a barley moon, the colder colors of the purpled sunsets. And yet, autumn is the hardest season for me to love. Like many people, as the hours of daylight recede, I struggle with fatigue and a spiritual heaviness that only increases with my restless inability to accomplish anything. The medievals thought that the planet Saturn, Infortuna Major, governed the season of winter; they also thought that it brought sickness and the onset of old age. There’s something definitively Saturnine, leaden and infected, about my struggle to cling to joy as the days shorten in their draw towards the Winter Solstice.

My solution has, for several years, been to find a hiding place, some place where a combination of distraction and isolation stills the brittleness I so often feel around people at this time of year. As I’ve gotten older, that place has shifted from my bedroom floor and the comfort of fiction to a room with a view: someplace outside or looking on the outside where I can feel the chill wind and watch the light fade out of the empty sky, wanting less to be distracted now than to be taken out of myself.

I haven’t quite found a place yet this year, but last November, I had a fountain.

In the second of six living situations that made up a housing odyssey last year, a friend and I lived with a couple in a newly developed neighborhood, still mostly surrounded by construction and highway. The houses are tall and narrow, pressed up against each other like infinite points extending into a breadthless line, only separated by small yards and curving alleys in which to park your car. In the center of the neighborhood, the street curves like a ring. The thin houses surround it and in the center is a small bowl of grass, cut on one side by a stone ledge and half-hearted shrubbery. In the middle of the bowl is a small pond with a fountain, the identical twin of every water fixture you encounter in a newly constructed neighborhood.

This was my room with a view. There was a park nearby, a more beautiful place, with glorious red-vined trunks and trails that took you back into hilly fields and secretive community gardens, but I only went there when I felt caught up in the fiery colors and the Presence of God and the sheer joy of being alive. I went to the fountain when I needed to escape.

I would go in the late afternoon as the sky was greying but still light. I went when I needed a break from the Red Bulls and stacks of books—Charles Williams, the history of opera, Freud. Or if I came home late, I would park on the curve of the street and walk down to the fountain in a darkness softened by premature Christmas decorations and streetlights.

If it was dark, I would sit on the stone ledge, my boots hovering above the dark, barely shifting water. If it were still light out—and the circle was empty—I would lie on the grass near the water, hood up and hands in my pockets, to block both the cold and the real world.

I loved to look up at the sky—cold and grey and empty, pressing out to the corners of my vision like it wanted to consume everything in my line of sight. I would lie in the cold grass and watch the sky and think—about my family back home, or classes, or the smell of patchouli and how weird it is to miss someone you wanted to leave. I would think about Virginia Woolf and her stones and wish it were possible to walk down into the sky. I would lie and feel the blades of grass thick underneath my coat and let the feeling of emptiness seep out of me and into the cold earth and the white jet of the fountain and the wide grey sky, until I felt like I could breath again.”

I wrote those words my sophomore year of college. And these, the following fall.

“It has rained less since autumn started. Both here and at home in Iowa, the trees are more brown than red from the dry weather and the drought has dried up the Mississippi, peeling the water back to uncover the mud and calcified trees along its banks. The barges that usually carry corn and soybeans from the Midwest down to the Gulf of Mexico are stranded, grounded in the shallow river.

Every day I come home from school and lay across my bed, staring up at the slats above me. I’m always tired, no matter what I do. It feels like a chore just to breathe. Every week, I start out with the best intentions––sleep at least eight hours, eat something green, turn in every homework assignment––and in two days, I’m back on my bed, feeling like a cornhusk doll, dried out and rustling like dead leaves. I go to sleep anxious and wake ready to throw up. People talk to me and it feels like I’m listening from underground, their voices muffled as I try to shake the dust out of my ears. I can’t dig up any excitement over classes and every time I see a friend, I talk endlessly about how miserable I am.

I know I’m drying up but I don’t know where to find water.”

Aristotle called melancholia “a condition of feeling grief, but we cannot say what we grieve about.” I’m all too familiar with this condition; with the waves of sadness or exhaustion or despair that ebb and flow from season to season. My senior year of college, I wrote a familiar essay collection titled The Luminous and the Hidden, where I wrote about my conversion to Christianity, my journey as a writer, and my experience with intense depression and suicidal tendencies at the age of fourteen. Depression is a hard word for me to use. It feels like a dirty word, like a mark of shame, a “what’s wrong with me and why can’t I pull myself together?” kind of word. I grew up in a loving Christian home, safe from the substance abuse, broken relationships, or homelessness that scar so many people I meet. So how can I be sad? Depressive episodes—these waves of sadness that seem to come from nowhere and have no cause—don’t fit the persona I want to project to others, that I feel like I should embody, that I’m someone who is friendly and happy and whole.

I grew up in a loving Christian home, safe from the substance abuse, broken relationships, or homelessness that scar so many people I meet. So how can I be sad? Depressive episodes—these waves of sadness that seem to come from nowhere and have no cause—don’t fit the persona I want to project to others, that I feel like I should embody, that I’m someone who is friendly and happy and whole.

Charles Wright, in his poem “Apologia Pro Vita Sua”, wrote:

“There is forgetfulness in me which makes me descend

Into a great ignorance,

And makes me to walk in mud, though what I remember remains.”

I understand that, just as I understand Jocelyn’s streak of sadness. When I read the above passage on his “bias towards sadness”, I cried because I felt ashamed to be an endurer of life. I have friends who, like Felicity, seem to have been born under dancing stars, who invite others into their visceral joy, who love others easily because their natures tend toward everything in love. I have other friends who, like Grandmother, know their work and go to it, with the faithfulness of a life deeply rooted in God. Why then do I so often walk through mud, wading just to get to the next day, fighting just to stay afloat against waves of despair? Why do I, like Ferranti (who is, of course, the other character with whom I identify) see struggle and pain more easily than Beauty?

I don’t know, because these questions are not easily answered. But as I meditate on these things, I turn back to A City of Bells and it continues to cut deep. When Jocelyn first begins to explore Ferranti’s story, he feels “as though the thread of his own life was woven with that of another, a light thread with a dark, and until both of them were light he could not feel at peace.” Goudge picks up the image of the thread again, when little Henriette is kneeling in the chantry by the tombs of the dead.

“As she got up and dusted her knees, Henrietta realized how the invisible world must be saturated with the stories that men tell both in their minds and by their lives. They must be everywhere, these stories, twisting together, penetrating existence like air breathed in to the lungs…[Every] action and thought is a tiny thread to mar or enrich that tremendous tapestried story that man weaves on the loom that God has set up…”

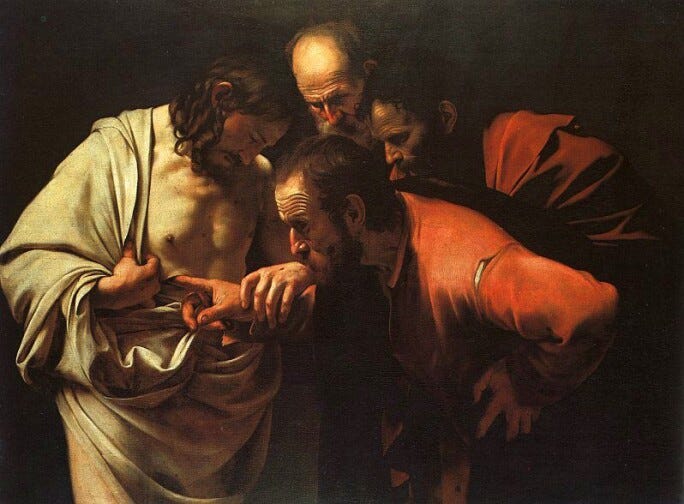

And God weaves threads of light and dark into all our lives. No life is without suffering and brokenness, nor without the Good and the Beautiful. In his book The City of God, St. Augustine compares the story of mankind to a poem, in which God allows suffering as rhetorical antithesis, so that beside it our redemption may shine more brightly. In painting, artists have a similar technique: chiaroscuro, or the contrasting use of light and shadow. One master of chiaroscuro was the Italian painter Caravaggio, whose dark and sometimes brutal paintings earned controversy in his day.

I love Caravaggio, because, like Ferranti, he strikes me as a man who looked at the world with his eyes open and didn’t flinch. His paintings show suffering; they show ordinary people in pain and sometimes in gruesome agony. A murderer himself, Caravaggio had experienced the darkness of the world and he painted it—literally. But neither are his paintings devoid of light. Look at his painting of St. Thomas and the risen Christ—the light falls softly on the faces of the men and the hand that probes Christ’s wound, drawing our attention to the gory proof of Resurrection.

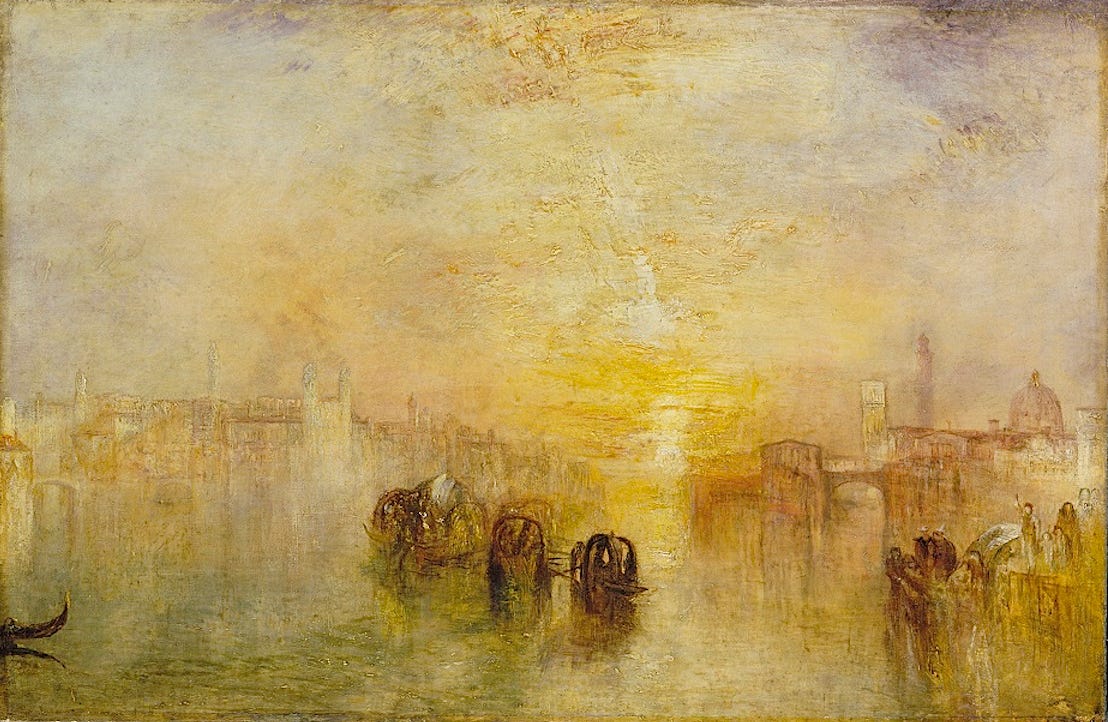

My other favorite painter is J. M. William Turner, for reasons wholly opposite. I love how Turner paints light, like he can’t get enough of it. Gold and blue and red radiate from his paintings in strokes and swirls of glory. He paints a world illuminated, a world alive with light. If we look between Caravaggio and Turner, who is the lover of the world, who the endurer of it? Can we tell? One paints darkness, the other light, and both are threads in God’s loom, in His chiaroscuro tapestry of the cosmos.

At the start of my summer, I reread The Faerie Queene, sketching out the narrative backbone for my novel. There’s one scene that always strikes me in Redcrosse’s story, one particular moment that cuts deep. Despaire, who leads knights to hang themselves, has Redcrosse in his cave and has convinced him that God had condemned him to He and he deserved to die. Redcrosse lifts a dagger, preparing to take his life—and then Una snatches it away and reprimands him, saying:

“In heavenly mercies, hast thou not a part?

Why shouldst thou then despeire, that chosen art?

Where justice grows, there grows eke greater grace,

The which doth quench the brond of hellish smart,

And that accurst handwriting doth deface.”

Or, as Charles Wright continues in his poem:

There is forgetfulness in me which makes me descend

Into a great ignorance,

And makes me to walk in mud, though what I remember remains.Some of the things I have forgotten:

Who the Illuminator is, and what He illuminates;

Who will have pity on what needs have pity on it.What I remember redeems me,

strips me and brings me to rest,An end to what has begun,

A beginning to what is about to be ended.

Chiaroscuro again, the dark thread and the light, the intertwining of a Divine Goodness with our broken world. And those of us who are endurers of the world add our verses to God’s poem and He reminds us that we serve a Lord “Who will have pity on what needs have pity on it.” So Jocelyn steeps himself in Ferranti’s poem and I steep myself in A City of Bells, finding a portrait of life in which sadness isn’t plastered over with fake smiles, but winds itself, line by line, into a greater poem. And I learn to trust that God weaves my dark thread beside the light, my feeble verses in His magnum opus, to one day turn my streak of sadness into joy.