Whatever Stuff Our Souls

On tragedy, true love, and the romance of Wuthering Heights

I was a senior in high school when I first read Wuthering Heights, and it seemed to have been written for me. I was seventeen; I had a shagged mullet and heavy eyeliner; my idols were Patti Smith and Grace Slick; my Spotify listening was The Smiths’ “There Is a Light” and Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart” on repeat. I was also deeply entangled in my own Emily Brontë-esque romantic turmoil, torn between the tall, quiet guy I’d had an unrequited crush on for the past two years and an on-again, off-again thing with a guy I’d met at a camp, a guitarist who wrote songs about me and took me on my first real date. Enter Wuthering Heights: moody, dramatic, intense; the epitome of pathetic fallacy in its lashing thunderstorms and windswept moors. I loved it. Teenage girls have a taste for the Gothic like no one else: Jekyll and Hyde, Frankenstein, Dracula, and, of course, the Brontë sisters. There’s a little Catherine Morland in all of us at that age, and I was no exception.

In my experience, Wuthering Heights has a reputation as a “teen girl novel” among literary people. Everyone loves Jane Eyre. I’ve had friends tell me that Anne Brontë is actually the best novelist of the three. But if Wuthering Heights gets read outside of high school, it’s usually in one of two ways: as a cliché example of Gothic literature (Look! Ghosts at the window! Byronic heroes! The moors) or as the intense and disturbing story of two psychotic lovers. Even when read by teachers or lovers of literature, the novel is treated like one of those dark “romantasy” books that now haunt the shelves of every bookstore known to man, thanks to Booktok. In other words: as teen girl fiction. Which is exactly what I expected when I decided to reread it this spring.

I was surprised, then, when I loved it as much as ever. In fact, I enjoyed it so much that I spent a Sunday afternoon curled up on the couch, so absorbed that I didn’t notice four hours disappear. (The last time I read like that was revisiting Jane Eyre last spring—and the last time before that was probably back in high school.) But I couldn’t immediately name what it was that I was enjoying, beyond the realization that the plot still gripped me and the characters still fascinated me. To that end, I’ve spent the past few weeks asking myself: what do I like about Wuthering Heights? And: what does it remind me of?

The question prompted a longer, twistier rabbit trail than I expected, involving Shakespeare, Aristotle, and Elizabeth Gaskell, among others—a little like a literary whodunnit, except instead of murder suspects, the cast contained every other author that came to mind as I read the novel. Rather than disagreeing with my teenage impression, I finished the novel convinced Emily Brontë was a brilliant novelist and should be read and taught—if not quite as often as Charlotte—more often than she is. This essay is an attempt to explain why.

Part One: The Bard

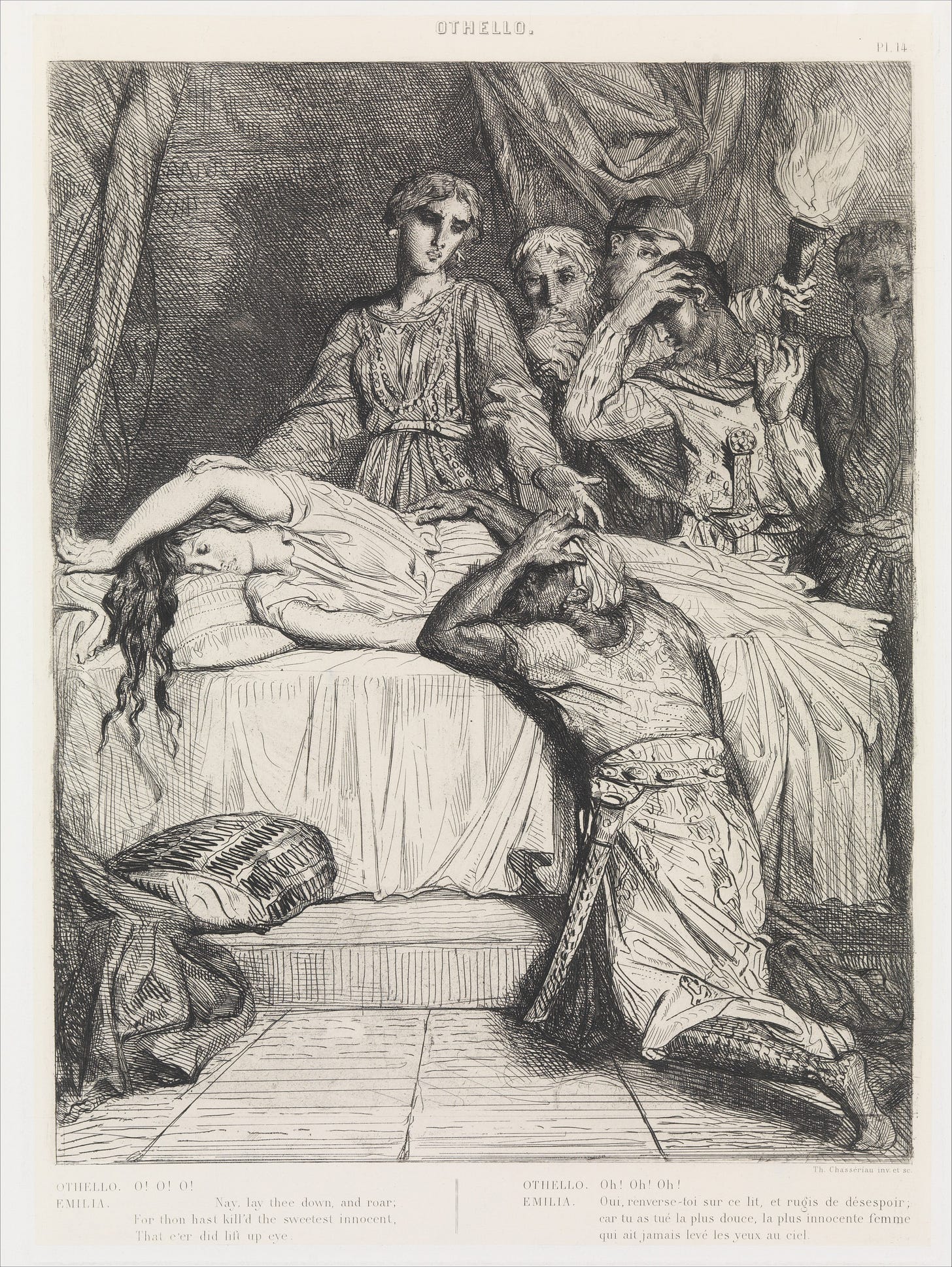

Halfway through my reread, the novel began to feel familiar (and not just because I’d read it before). A cast of characters involving (multiple) ill-fated lovers, ghosts, feuding families, and a loyal servant who sometimes seems like the only one with any common sense? Shakespearean archetypes, one and all. As it grasps the window in Lockwood’s dream, Catherine Earnshaw’s ghost resembles a sort of Banquo, tormenting Heathcliff, or the Weird Sisters or Hamlet’s father, as the spectral apparition of fate that opens the story. (In this case, by inspiring Lockwood’s curiosity about the Earnshaw family.) Catherine is herself a sort of Regan or Goneril: beautiful, but destructive in her need to have whatever she wants. Not that she is wholly unsympathetic, especially as a child, but like so many tragic figures, she has a greatness—in this case, the intensity of her love and her ability to make others love her—that, coupled with moral failure, pulls to pieces the lives of everyone around her. Nelly Dean is a homelier, Yorkshire version of the faithful servant—Paulina from A Winter’s Tale, maybe—who does her best to ward off ruin. And Heathcliff is perhaps Othello, “the vengeful Moor.”

In other words, as I read I found myself in the middle of an old, archetypal plot, that could only be called Shakespearean. We know that the Brontës read Shakespeare as children, while Emily and Anne’s imaginary world of Gondal featured dramatic characters (monarchs, soldiers, lovers) and plots (assassinations, wars, and complicated love affairs) that echo Macbeth, As You Like It, Romeo and Juliet, and others. It seems likely that Shakespeare’s plays were the soil in which Wuthering Heights took root.

So far, I’ve named parallels between Wuthering Heights and King Lear, Macbeth, and Othello. This was the second thought that struck me as I reread the novel: that it was not only Shakespearean, but also tragic. Like so many tragedies, Wuthering Heights revolves around the misery and violence of a particular family. Of Shakespeare’s great tragedies, Lear, Othello, Romeo and Juliet, and Hamlet are all stories of family conflict, while Macbeth and Julius Caesar depict the disintegration of the polis and of friendships, which are the natural extensions of the family sphere. I couldn’t help but think of the opening lines of Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

The story of the Earnshaws and Lintons is the story of an unhappy family: Catherine’s relationship with her father, how Hindley governs the house after Mr. Earnshaw’s death, the death of Hindley’s wife, Catherine’s refusal to choose between Edgar and Heathcliff, Hindley drinking and gambling away his and his son’s family home, Isabella’s marriage to Heathcliff, Heathcliff’s treatment of his son and Edgar’s daughter. The house that Lockwood enters at the start of the book is unwelcoming, inhabited by personalities wholly unlike the ones he expects from polite society:

“[We] at length arrived in the huge, arm, cheerful apartment, where I was formerly received.

It glowed delightfully in the radiance of an immense fire, compounded of coal peat, and wood: and near the table, laid for a plentiful evening meal, I was pleased to observe the ‘missis’, an individual whose existence I had never previously suspected. I bowed and waited, thinking she would bid me take a seat. She looked at me, leaning back in her chair, and remained motionless and mute.

‘Rough weather!’ I remarked. ‘I’m afraid, Mrs. Heathcliff, the door must bear the consequence of your servant’s leasure attendance: I had hard work to make them hear me!’

She never opened her mouth. I stared—she stared also. At any rate, she kept her eyes on me, in a cool, regardless manner, exceedingly embarrassing and disagreeable.

…Meanwhile, the young man had slung onto his person a decidedly shabby upper garment, and, erecting himself before all the world as if there were some mortal feud unavenged between us. I began to doubt whether he were a servant or not; his dress and speech were both rude, entirely devoid of the superiority observable in Mr and Mrs Heathcliff.”1

Heathcliff is savage, Cathy haughty, Hareton sullen. Lockwood’s first encounter with Wuthering Heights is the portrait of an unhappy family. We are thrust with him into the dismal scene, but none of us know yet the brutal history of the Earnshaw family and of Heathcliff’s role in it. As he questions Nelly Dean, the story rewinds, and we watch the Earnshaw and Linton families collapse over the years, until we are brought back up to the present day, and the bleakness of the family scene makes sense.

Having begun, then, to think of tragedies, I turned to Greek drama. How many of the ancient plays are about unhappy families? Several: Euripides’ Medea and Iphigenia at Aulis, Aeschylus’ Oresteia, and Sophocles’ Oedipus trilogy, but especially Antigone. In order, then, to discuss what elements make a tragedy a tragedy, and apply them to Wuthering Heights, I knew I needed to visit an old friend.

Part Two: The Philosopher

I first read Aristotle’s Poetics as a freshman in college, a year after my introduction to Wuthering Heights. I had shorter hair, but the same preference for sad music, while nothing had come of my high school romantic angst. The Poetics was our first assigned reading of the semester, to prepare us for a unit on Greek drama. Poetics is one of the earliest works of aesthetic theory (and to my knowledge, the first complete one); in it, Aristotle defines terms that become the fundamental tools of storytelling: plot, action, character, resolution, and so on. Tragedy, he says, is: “an imitation of an action that is admirable, complete and possessing magnitude; in language made pleasurable, each of its species separated in different parts; performed by actors, not through narration; effecting through pity and fear the purification of such emotions.”2

To paraphrase in slightly more familiar language: “A tragedy is a story about something that astonishes us; a whole story, something larger-than-life, told well, by showing and not telling, that makes us pity those who suffer and reminds us that fearful or sorrowful things can happen to us as well, but along with such a reminder, gives us a framework in which to order and understand the tragic events in our own lives.”

He then goes on to name two specific elements of a tragedy: “reversal”, which he calls “an action producing the opposite effect from what the actor intended” and “recognition”, which is a “change from ignorance to knowledge, disclosing either a close relationship or enmity, or the part of people marked out for good or bad fortune.”3 In other words, friction makes for a good tragic plot. The character doesn’t get what he wants; actions follow as natural consequences of his choices, but contrary to his desires. Something happens that is unexpected, or some revelation throws everything into turmoil. Things don’t go smoothly for the characters, which is the foundation of all good plot.

Nowhere in his formula does he specify that good tragedy focuses on a familial plot, but looking at the elements Aristotle describes, it makes sense that so many dramatists chose plots about families: fathers and daughters, husbands and wives, brothers and sisters. According to Aristotle, one of the goals of the tragedian is unity in his work: unity of place, time, and plot. A family has a greater degree of “unity” than other relationships; it’s more insular, more self-contained. A plot about someone suffering at the hands of his family members, like Lear, or being torn between loyalty to two parents, like Orestes, heightens the emotional intensity of a story. The stakes are higher, because the protagonist can’t un-involve himself from his own family. However he acts, it will come back on his head too.

Emily clearly had a touch of the dramatist in her. Of the poems written in her youth, once assumed to be about her own love life or secret heartbreaks, a number have turned out to be monologues written from the voice of various characters from her imaginary world of Gondal. This dramatic tendency shows up in Wuthering Heights as well. The entire story takes place in two houses and their adjoining land, creating a compactness of setting of which Aristotle would have approved. The plot hinges on a series of reversals: Catherine’s conversation with Nelly Dean, in which she can’t decide between Edgar and Heathcliff, causes the latter to leave Yorkshire, and Heathcliff’s return leads to Catherine’s death; both results contrary to the wishes of the actors. By choosing to create a secondary narrative around the story—Nelly Dean’s conversation with Lockwood—Emily also heightens the moments of recognition with dramatic irony. We know before Isabella does what sort of person Heathcliff is; we know before Cathy what her relation to Hareton is, or where Linton disappears to, or what Heathcliff’s scheme for the cousins is.4

Emily does deviate, however, from Aristotle’s guidelines in her composition of characters. Nobody in Wuthering Heights fits Aristotle’s requirement that tragedy portray people “better than we are.”5 Rather, they all resemble the sort of people that Elizabeth Gaskell described when she visited the Brontë’s childhood home:

“These men are keen and shrewd; faithful and persevering in following out a good purpose, fell in tracking an evil one. They are not emotional; they are not easily made into either friends or enemies; but once lovers or haters, it is difficult to change their feeling. They are a powerful race both in mind and body, both for good and evil.”6

And, speaking of the remoteness of the area:

“[What] strange eccentricity—what wild strength of will—nay, even what unnatural power of crime was fostered by a mode of living in which a man seldom met his fellows, and where public opinion was only a distant and inarticulate echo of some clearer voice sounding beyond the sweeping horizon.”7

And again, in a quote that could summarize the whole of Wuthering Heights: “A solitary life cherishes mere fantasies until they become manias.”8

Wuthering Heights is then a Shakespearean drama, reminiscent of Aristotelian conventions, but rooted in the eccentric, strong personalities that Emily knew well. Heathcliff is not an Aristotelian hero, but he is an archetype of this “powerful race.” Others have drawn parallels between Heathcliff and Lord Byron, but it is more likely that inspiration for the character sprang from her local context. But Emily’s novel is, of course, a Gothic one, echoing and foreshadowing other nineteenth century works like the poetry of Lord Byron, as well as Dracula, The Woman in White, and her sister’s own Jane Eyre. But it reminded me of two authors and two works in particular, which leads us to…

Part Three: The Monster and the Albatross

Romanticism and Gothic literature have an interesting relationship: like two pools, which flow in and out of each other, but remain distinct. Both literary movements share a strong medieval influence, supernatural elements, and settings which make Nature into its own actor and personality. They have their differences, though: Romanticism encompassed not only literature, but also philosophy and poetic theory, while Gothic literature stayed rooted in the novel. (We can talk about Romantic philosophers, but not Gothic ones.) And though both emphasize the otherworldly and the outbreak of strong emotion, the Romantic expression of it is slightly different than the Gothic: the ouranic versus the cthonic, perhaps. Not all Romantic authors are Gothic, or vice versa. Schiller, Goethe, Wordsworth—Romantic. Dracula, Jekyll and Hyde, Poe’s short stories and poetry—Gothic.

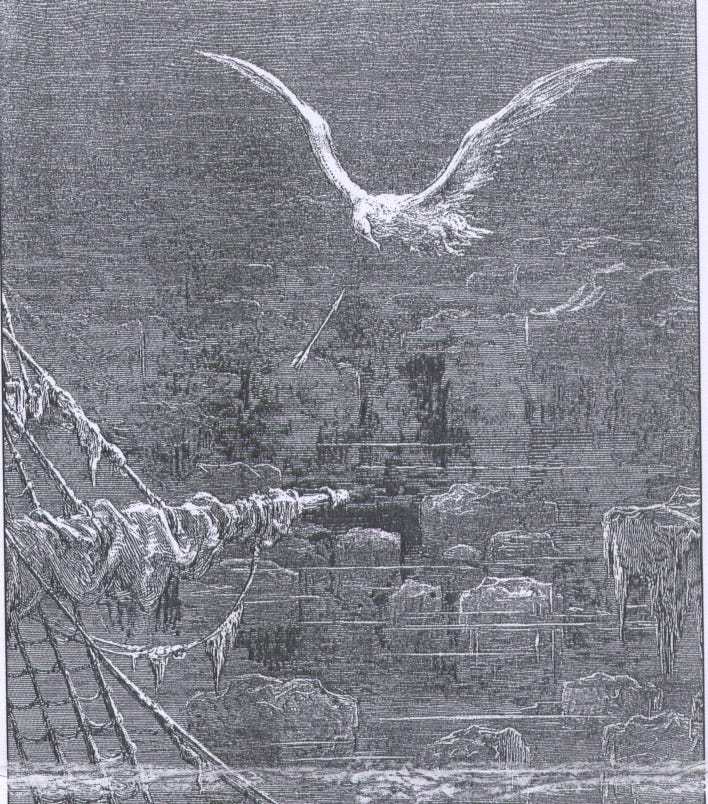

Then there are the authors who combine the higher notes of Romantic philosophy with the dark undercurrent of Gothic literature. Coleridge does so in his Rime of the Ancient Mariner, where the supernatural—the northern daemon, the death of the albatross, the ship of Death—symbolizes the mariner’s spiritual journey, culminating in his final adjuration to the young wedding guest. Similarly, in Frankenstein, the Gothic elements, from the Monster’s creation and its pursuit of Frankenstein to the murders it commits, serve not only to create the atmosphere found in all Gothic literature, that “there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy”, but also to grapple with a Romantic line of questioning: what is nature? What are its limits? Is evil inherit in it or produced?

Emily Brontë picks up this same line of questioning in Wuthering Heights. In the twenty-first century, we’re more likely to credit social evil or broken family structures for producing criminals than a certain kind of “nature”. Brontë’s Victorian audience would’ve come from the other direction: phrenology was in full swing, people were fascinated by criminal psychology, and, as we see in Jane Eyre, even children were suspected of having “bad natures” if they didn’t behave the way adults wanted. Hindley and Mrs. Earnshaw, the Lintons, and the rest of their small community all alienate the child Heathcliff, who looks “dark almost as if [he] came from the devil”, as Mr. Earnshaw says.9 Like Frankenstein’s Monster, mystery surrounds Heathcliff’s arrival, and like the Monster, his appearance and origin sets a barrier between himself and the normal community. When Catherine decides to marry Edgar, Heathcliff disappears for three years and returns, now wealthy and determined to enact his revenge, especially on Hindley.10 The unusual nature of his arrival, disappearance, return, and death create a character reminiscent of the archetypal “devil at the crossroads,” who appears, tries to trap souls, and vanishes. Yet Emily, like Shelley, leaves the door open on the question of Heathcliff’s “nature” and whether the assumption that he is devilish, even as a child, shapes his decision to become so. And like Coleridge, her use of folklore serves not only as good storytelling, but also to create the spiritual atmosphere of the novel.

But more on that in…

Part Four: A Prince in Disguise

As I read, I first imagined the novel as a tragedy. But by the time I finished it, I changed my mind; a different form had suggested itself instead. Earlier in the essay, I listed a number of parallels between the novel and various Shakespeare plays. Then I said I had named Macbeth, King Lear, Othello, and Hamlet, and proceeded to talk about tragedy. “But wait—” you maybe thought— “You also mentioned A Winter’s Tale.”

I did. And it is A Winter’s Tale, I decided, that sets the real pattern for Wuthering Heights. Ultimately, it is not a tragedy, but a tragedy that ends a comedy, which is to say, a romance. I’ve already quoted the scene where Lockwood first arrives at Wuthering Heights. We see there, in sullen Hareton and spiteful Cathy, our Florizel and Perdita: a prince and princess in disguise, not only in coarseness of appearance, but in coarseness of manner. The tragedies of the earlier novel—the violence and misery of their unhappy families—have buried their true natures. Unaware that the mastery of Wuthering Heights was stolen from him by Heathcliff, Hareton is content to be uneducated and ignoble; he expects no better from himself. Beaten down by her forced marriage to Linton and harsh treatment from Heathcliff, Cathy’s natural affection, seen earlier in her deep love for her father Edgar, has dried up. Hareton and Cathy are, like so many characters in the novel, unhappy and unlikable people.

How much more powerful, then, is the scene that Lockwood finds when he returns a second time to Wuthering Heights:

“I had neither to climb the gate, nor to knock—it yielded to my hand.

That is an improvement! I thought. And I noticed another, by the aid of my nostrils; a fragrance of stocks and wall flowers, wafted on the air, from amongst the homely fruit trees.

Both doors and latices were open; and yet, as is usually the case in a coal district, a fine, red fire illumined the chimney; the comfort which the eye derives from it, renders the extra heat endurable. But the house of Wuthering Heights is so large, that the inmates have plenty of space for withdrawing out of its influence; and, accordingly, what inmates there were had stationed themselves not far from one of the windows. I could both see them and hear them talk before I entered, and looked and listened in consequence, being moved thereto by a mingled sense of curiosity, and envy that grew as I lingered.

‘Con-trary!’ said a voice, as sweet as a silver bell— ‘That for the third time, you dunce! I’m not going to tell you, again— Recollect, or I pull your hair!’

‘Contrary, then,’ answered another, in deep, but softened tones. ‘And now, kiss me, for minding so well.’11

The atmosphere is wholly different, and the reason is obvious: Cathy and Hareton have fallen in love. There is a clear parallel between their story and Heathcliff and Catherine’s: Cathy has her mother’s passionate nature and Hareton is, ironically, Heathcliff’s heir, raised by him and having the same force of personality that Gaskell described in the Yorkshire men. But there are also differences between the two couples. Cathy has the kind of personality that needs to love and be loved, but she isn’t selfish or possessive like her mother. Rather, she acts towards Hareton in a way that Catherine couldn’t towards Heathcliff. Catherine refuses to let Heathcliff go, even after her marriage to Edgar, and blames him for her unhappiness and death. In contrast, Cathy humbles herself and asks for Hareton’s forgiveness: “I didn’t know you took my part,” she says;“and I was so miserable and bitter at everybody; but, now I thank you, and beg you to forgive me, what can I do besides?”12

Meanwhile, Hareton has been treated exactly as Heathcliff was as a child: shunned and humiliated, treated as a servant, rather than part of the family. Furthermore, he’s been kept from the role of gentleman that would’ve been his by birth. And yet unlike Heathcliff, he has no desire for revenge. He refuses to hear Cathy accuse Heathcliff, and when Heathcliff dies, Hareton is the only one who mourns him. But while Heathcliff is alive, and long before Cathy makes any gesture of friendship, he defends her from Heathcliff, “taking [her] part a hundred times.”13

In doing so, he proves himself to be not only Heathcliff’s superior, but also his father Hindley’s, exerting himself to protect those in his household. Comparing Hindley and Edgar Linton, Nelly Dean says:

“They had both been fond husbands, and were both attached to their children; and I couldn’t see how they shouldn’t both have taken the same road, for good or evil. But, I thought in my mind, Hindley, with apparently the stronger head, has shown himself sadly the worse and weaker man. When his ship struck, the captain abandoned his post; and the crew, instead of trying to save her, rushed into riot and confusion, leavning no hope for the luckless vessel.”

In contrast, Hareton becomes, like Edgar, and unlike so many of the other characters, the helmsman of his life; he is inspired to this degree of mastery in part by his affection for Cathy, and in return, she elevates him to inhabit his new role well. “You know,” Nelly Dean tells Lockwood,

“they both appeared, in a measure, my children: I had long been proud of one; and now, I was sure, the other would be a source of equal satisfaction. His honest, warm, and intelligent nature shook off rapidly the clouds of ignorance and degradation in which it had been bred; and Catherine’s sincere commendations acted as a spur to his industry.”

There are endless fairy tales about the transformation of an apparently unworthy hero or heroine into the true prince or princess: Beauty and the Beast, Catskin, East of the Sun and West of the Moon, Bearskin, or even Oedipus again, where Oedipus is raised as a shepherd instead of as a prince. In fairy tales, the disguise is usually the result of some curse; in Wuthering Heights, the curse is everything that’s happened in the Earnshaw and Linton families and the work of Heathcliff’s revenge. And in typical fairy tale fashion, it is a curse undone by love.

As I finished the book, the opening lines of Romeo and Juliet came to mind:

“From forth the fatal loins of these two foes,

A pair of star-crossed lovers take their life,

Whose misadventured, piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents' strife.”

So too in Wuthering Heights, only Cathy and Hareton “bury their parents’ strife”, not by their deaths, but by their love. It is this plot arc—the new recognition of their true identities through mutual support and the reversal of their unhappy families’ bitterness and misery—that I so enjoyed as I reread the novel. It is also what I loved so much about it as a seventeen-year-old.

There are teenage girls who idolize Catherine and Heathcliff’s love, I’m sure. But I wasn’t one of them, nor have I ever met one in real life. Of course, when Catherine and Heathcliff were teenagers, my seveteen-year-old self wanted them to get together, and of course I copied Catherine’s famous “He is more myself than I am. Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same” down in my journal. But when Heathcliff came back from his long disappearance eager for revenge, and particularly following his treatment of Isabella (and then Cathy), any sympathy I had for him quickly disappeared. I remember being frustrated with Catherine too, for not having the moral strength to pick a guy and leave the other one alone. (A little ironic, considering my own teenage love triangle predicament, but then again, I wasn’t married to either of them.) When I talked to a sixteen-year-old recently about her first read of Wuthering Heights, her response was the same: Heathcliff made her uncomfortable, Catherine was frustrating, but Hareton…Hareton you could root for.

I’m curious, then, why so many people read Wuthering Heights as if Emily meant for us to admire Heathcliff and Catherine’s romance. For Emily to truly believe that Heathcliff and Catherine were some kind of fated soulmates, who did the right thing by putting their passion for each other on a pedestal above everything else, she would have to believe that it was moral for Catherine to cultivate a love affair with Heathcliff as a married woman, that Heathcliff’s treatment of Isabella, Hindley, Hareton, his own son, and Cathy was something easily shrugged off, and that Edgar, who is later shown to be a devoted father and the source of Cathy’s caring personality, was only a laughable obstacle. But reading Wuthering Heights through such a lens supposes an anachronistic degree of moral relativism and idolization of one’s personal feelings. Emily Brontë is not a twenty-first century romantasy author. Rather, Wuthering Heights is a work more akin to its sister, Jane Eyre: unconventional, certainly, but nevertheless rooted in a moral framework. We read Shakespeare without assuming that because he can produce such characters as Lady Macbeth or Iago, he necessarily approves of their actions; people rarely read Emily Brontë with the same discernment. That she was fascinated by stories of strong personalities and destructive passion is clear, that she considered Heathcliff and Catherine to be an aspirational model of romantic love is not.

But then why does the novel end the way that it does? If Emily doesn’t intend for us to read Heathcliff and Catherine’s story as a picture of what romantic love should look like, why does the story’s end imply that they are reunited after death, wandering the moors as ghosts, together again like they wanted? If Wuthering Heights is actually a comedy, then by Aristotle’s definition, it should end with “opposite outcomes for better and worse people,” that is, with goodness rewarded and evil punished.14 So why doesn’t it?

In answer, I’ll just say: Catherine and Heathcliff’s reunion may have been what they wanted. It may also have been what they deserved. As Heathcliff draws closer to death, Nelly Dean describes him looking not like himself, but like “a goblin.”15 Elsewhere, he’s described as a ghoul, a vampire, or a fiend. To a modern reader, this means little. To a reader in Brontë’s time, steeped in the spiritual atmosphere of the Church, it reads as a warning. Again, modern academics interpreting Wuthering Heights may be tempted to read this as a devil-may-care description, with the monstrous or demonic language merely serving to remind us that Heathcliff and Catherine’s love is just so powerful and so important, even though it seems dark and unnatural to others. I find it hard to read older authors as so intentionally subversive. Gothic writers depicted immoral characters, wicked schemes, or dark supernatural elements against the background of normal moral sentiment. It’s hard to write a thrillingly wicked character if you think that what he’s doing isn’t really so bad after all. That Emily Brontë could create a Heathcliff implies that she had something to compare him to.

How then should we interpret the ending of Wuthering Heights? If it reminds me of anything, it reminds me of Francesca and Paolo in Dante’s Inferno, trapped together in a whirlwind for all eternity, because they couldn’t untangle their passion for each other in life. They may be together, but they are not happy. Heathcliff dies peacefully on earth, because he believes he is going to be with Catherine. Whether he wakes to peacefulness after death is a different question. To return again to Shakespeare, to Banquo or Hamlet’s father: a soul becomes a ghost precisely because it is not at rest, and so it may be that the novel ends with “opposite outcomes for better and worse people,” after all.

And as for the better outcome, we are given clear evidence that one of the couples at the end of the novel finds happiness, and it is Cathy and Hareton. As Nelly Dean tells it:

“The intimacy thus commenced, grew rapidly; though it encountered temporary interruptions. Earnshaw was not to be civilized with a wish; and my young lady was no philosopher, and no paragon of patience; but both their minds tending to the same point—one loving and desiring to esteem; and the other loving and desiring to be esteemed—they contrived in the end, to reach it.

You see, Mr Lockwood, it was easy enough to win Mrs Heathcliff’s heart; but now, I’m glad you did not try—the crown of all my wishes will be the union of those two; I shall envy no one on their wedding day—there won’t be a happier woman than myself in England!”

That one phrase—“one loving and desiring to esteem; and the other loving and desiring to be esteemed”—summarizes the superiority of Cathy and Hareton’s love over Catherine and Heathcliff’s. Romantic love should be ordered towards the good of the other person, but neither Catherine nor Heathcliff was capable of such an ordering. Cathy, on the other hand, wants to see Hareton as someone worthy of admiration, and pours her love into drawing out what is noble in him. The true romantic highlight of Wuthering Heights is not Catherine’s “Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same”, but this homophrosyne, “both minds tending to the same point,” that point being Hareton’s restoration to the role of gentleman and master of Wuthering Heights.

In closing, the point of this essay is not to argue all the Emily Brontë out of the novel. After all, the morbid humor and extreme personalities are part of what make the book interesting, as with a novel by Fitzgerald or Waugh. But there are other elements in Wuthering Heights that are often overlooked, just as Jane Eyre is sometimes read only through the lens of moral indignation at Rochester’s behavior, or strictly as a proto-feminist text, or from any number of perspectives that ignore character development, social and historical context, or Charlotte’s broader Christian ethic. When we read any literature as “one note”, we miss its full texture of meaning. Wuthering Heights is a much more interesting novel than it is always allowed to be, and this essay is my best attempt to explain why.

Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc, 2015), p 6-7

Aristote, Poetics, trans. Malcom Heath (London, England: Penguin Books Ltd, 1996), p 10

Ibid p 18

The use of a frame narrative to create suspense is a common Gothic trope.

Ibid p 25

Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Brontë (London: Penguin, 1997), p 18

Ibid, p 23

Ibid, p 23

Ibid, p 26

Which prompts me to wonder if Emily read The Count of Monte Cristo as it was being serialized.

Bronte, p 226

Ibid, p 230

Ibid, p 230. Though Hareton does smack Cathy at one point, after she drops all his books in the fire, because heaven forbid the Brontës write a man who’s entirely chivalrous. My sense with that scene is that it’s more like when I was a kid and would needle my brother until I crossed a line and once or twice got wrestled to the ground or thumped for it than the same kind of thing as Heathcliff’s treatment of Isabella. But on a scale of Mr. Knightley to “Mr. Rochester lying about that one very particular thing” as far as acceptable male behavior, Hareton’s definitely not towards the Austen end of the spectrum.

Aristotle, p 22

Bronte, p 242

"When we read any literature as “one note”, we miss its full texture of meaning."

Absolutely. I don't think they were ever meant to be read as such, and any story worth its salt is broader, deeper, wiser and more intuitive than the writer who brought it forth. I don't think it's ever our place to tell a story what it is, because it's not really within our ability.

I enjoyed your look through the book beyond its usual off-the-cuff analysis; I always believed there was more to it than what book club blurbs and EngLit essays may have suggested.

Your ability to position Wuthering Heights within its literary influences is masterfully done. I remember despising this book as a teenager because it had been hailed as a romance and it seemed rather a cautionary ghost story. I reread it recently as an adult and found myself marveling at the mood, scene, character development (and lack thereof), and enjoying the redemptive twist more than I did as a young person. I had never considered Cathy/Hareton as the protagonists and thus didn't categorize it as a comedy. Emily is my least favorite of the Bronte sisters but her writing is undeniably powerful. I truly enjoyed your literary analysis and unique perspective on a book I have loved to hate. Thank you!